Pathophysiology of Allergic Rhinitis: Immune Mechanisms Explained

Written by: Dr.Muhammad Ihsan Ullah, PhD

Medically reviewed by: Dr. Muhammad S. Anil, MD

Last updated on February 07,2026

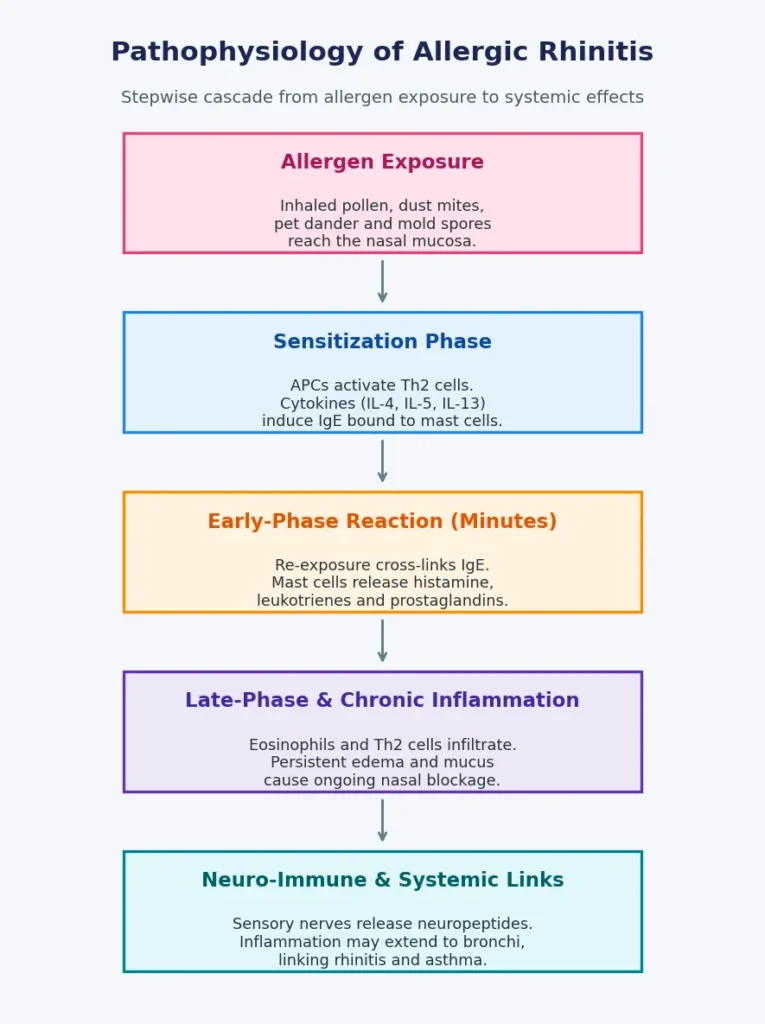

Allergic rhinitis is a complex immune-mediated inflammatory disorder of the nasal mucosa. It develops when the immune system mounts an exaggerated response to inhaled environmental allergens such as pollen, dust mites, mold spores, or pet dander. In genetically or environmentally predisposed individuals, exposure to these otherwise harmless particles initiates a cascade of immunological events that ultimately results in nasal inflammation and characteristic allergic responses.

Sensitization: The First Step

Sensitization is the initial immunological phase of allergic rhinitis and occurs after first exposure to an allergen. Initially, antigen-presenting cells (APCs), commonly the dendritic cells in the nasal mucosa, capture and process the allergen particles. These cells subsequently deliver allergenic peptides to T-helper type 2 (Th2) lymphocytes that produce cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13.

These cytokines activate B-cells to produce allergen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. The IgE molecules then adhere to mast cells and basophils, “priming” them for future exposures. Clinically, this period is silent; the person feels no symptoms, but the immune system has been prepared to overreact the next time.This process is known as the sensitization phase of allergic rhinitis, during which the immune system becomes primed for future reactions.

Early-Phase Allergic Reaction

The early-phase allergic reaction in allergic rhinitis occurs within minutes of allergen re-exposure.When exposed to the same allergen again, mast cell-bound IgE antibodies detect it and cause mast cell degranulation. This causes the release of potent chemical mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and cytokines into the nasal tissue.

These mediators cause:

- Nasal congestion and swelling due to vasodilation

- Sneezing and itching from sensory nerve stimulation

- Excess mucus production causing rhinorrhea

Late-Phase Inflammatory Response

The late-phase inflammatory response in allergic rhinitis develops several hours after allergen exposure. Inflammatory cells, including eosinophils, basophils, Th2 cells, and group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), infiltrate the nasal mucosa. These cells produce more cytokines and pro-inflammatory mediators, causing inflammation to persist even in the absence of continued allergen contact.

This chronic inflammation causes persistent nasal blockage, sinus pressure, and mucosal edema. Long-term, it can cause tissue remodeling, goblet cell hyperplasia, and collagen deposition, resulting in a more severe and persistent form of allergic rhinitis.

Neuro-Immune Mechanisms in Allergic Rhinitis

A recent study has shown that sensory nerve activity plays a role in the perpetuation of nose symptoms. Nerve endings in the nasal mucosa become hypersensitive, releasing neuropeptides that exacerbate inflammation, resulting in a vicious cycle of sneezing, itching, and congestion. This explains why people with allergic rhinitis are generally more sensitive to irritants like smoke, fragrance, and temperature fluctuations.This process contributes to neurogenic inflammation in allergic rhinitis, explaining heightened sensitivity to irritants.

Systemic and Lower-Airway Links

In allergic rhinitis, the inflammation spreads beyond the nose. Mediators secreted in the nasal passages can enter the bloodstream and affect the lower airways, which explains the common coexistence of asthma and rhinitis, also known as the “one airway, one disease” notion.This relationship explains the strong allergic rhinitis and asthma link observed in clinical practice.

Medical Review Disclaimer

This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The content is written by a qualified healthcare professional and medically reviewed for accuracy. However, it should not be used as a substitute for professional medical diagnosis, treatment, or advice. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider regarding any medical condition or health concern.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the basic pathophysiology of allergic rhinitis?

Allergic rhinitis is an IgE-mediated inflammatory reaction in the nasal mucosa triggered by inhaled allergens such as pollen, dust mites, pet dander, or mold.

2. What is sensitization in allergic rhinitis?

Sensitization is the initial phase in which allergen exposure leads to Th2 activation, cytokine release, and production of allergen-specific IgE that binds to mast cells and basophils.

3. What happens during the early-phase allergic reaction?

Within minutes of re-exposure, mast cells degranulate and release mediators like histamine, causing sneezing, itching, nasal congestion, and rhinorrhea.

4. What is the late-phase response in allergic rhinitis?

Several hours later, cells such as eosinophils and Th2 lymphocytes infiltrate the mucosa, maintaining inflammation and contributing to persistent nasal blockage and tissue remodeling.

5. How is allergic rhinitis linked to asthma?

Shared inflammatory pathways mean that mediators from the upper airway can affect the lower airway, supporting the “one airway, one disease” concept and explaining the frequent coexistence of asthma and rhinitis.